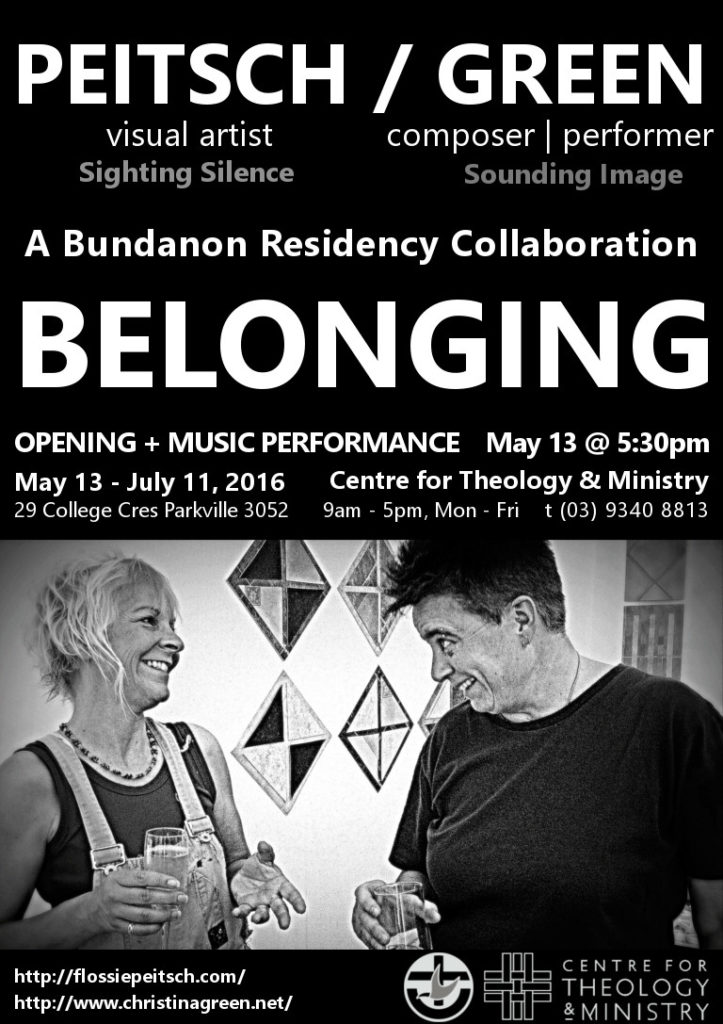

To Belong or Not to Belong

by Neal Nuske

Opener and Essayist for BELONGING, CTM, May 2016

To belong or not to belong – that is only one of the questions: When? With whom? Where? Under what circumstances? For how long?

Neal Nuske, Bachelor of Theology Luther Seminary Adelaide; Bachelor of Educational Studies and Master of Educational Studies (Research) The University of Queensland, St Lucia; Graduate Diploma Social Science (Counselling) QUT Carseldine, Brisbane; Associate of Music, Australia (Piano Performance).

In July 1890, Vincent van Gogh revealed his being on canvas in the form: Wheat Field Under Clouded Sky. In his later works, according to art critic Robert Hughes, he was yearning for ‘concision and grace’. According to Edwards, his life was ‘a quest for unification, a search for how to integrate the ideas of religion, art, literature, and nature that motivated him.’ He was a human being who frequently crossed the no-man’s-land between belonging and isolation, between fragmentation and disintegration, between alienation and intimacy, between confidence and apprehensiveness. While never resolving these paradoxes nor experiencing a peace which passes all human understanding, nevertheless, his sense of self wrought some momentary solidity of form when implanted on the canvas shrouded in the colours of the natural world. Wheat Field Under Clouded Sky was one of more than a dozen works around these themes. His prolific output is testimony to the intensity and creativity energising the search for belonging and peace. Van Gogh concluded: One does not expect to get from life what one has already learned it cannot give.

Life has a habit of presenting human beings with moments characterized by unexpected disruption, unwarranted disequilibrium and bewildering disturbance. My own sense of belonging in the world was radically challenged and disrupted by the onset of cancer at age 12 when a chondrosarcoma, otherwise known as a soft-tissue cancer, took up residence, or, found a place it called ‘home’ and exploited its sense of ‘belonging’ in my body. Consequently, surgery was necessary to dislodge this unwanted and unwelcomed ‘resident’ even though it was inspired and formed out of my own genetic material and successfully nourished by my very own biological resources.

However, all the checks-and-balances necessary for belonging to life itself were skewed in the direction of non-being or death. “Am I going to die?” is a question a twelve-year old child is not yet equipped to contemplate. The resulting surgical intervention in the form of a transpelvic-hemipelvectomy, while both life-taking and life-giving, left me with the challenge of whether or not I wished to continue belonging in a mutilated body with the prospect of making choices about how I would navigate and negotiate my way through life: in other words, belong in a familiar world from which I began to feel estranged, differentiated and alienated.

Although I did not know it at age 12, I had already discovered what the noted theologian Paul Tillich referred to as the “essential doctrine of freedom”, that is, that aspect of being human which enables us to make a choice and create an essential structure around our self, both body and mind, which is empowering to the degree it gives us the courage-to-be, the courage-to-belong in a different form. In my case, this meant a decision to continue living in an unfamiliar and radically different physical form. Each person can choose a particular way to relate to the givens of existence. Such a choice begins the search for belonging.

Here Peitsch and Green, within their works, permit bits and pieces of their inner selves to find form in various mediums or themes. Their creations join Van Gogh’s wheat fields through installation, or symbols, or sounds, or shapes. As with Green, in the case of the composer, the self is initially inspired and then comes into being the moment the first notation is made; then it is played. When the final bar is completed, the self disappears and remains in silence, imprisoned behind bars and coded in notation. It requires another performer to cross the no-man’s-land between silence and sound.

The givens of my existence, the reality of cancer and its consequences, had thrust upon me the necessity to decide whether or not I wanted to belong to the world I previously inhabited, to live within what was left of my body and to decide how I would cope in the world outside of Ward 2D Brisbane General Hospital. In 1963 this was my Umwelt, or my sustaining and healing environment. My twelve-year old mind was struggling to interpret my shattered world. Not only that: I also had to consider how I would ‘fit’ within the world of my fellow human beings. How I could possibly live within the world of interpersonal relationships, my Mitwelt, a world to which I belonged but at the same time felt estranged? Finally, I wondered how I was going to learn to live within my ‘self’ which was experiencing a radical crisis in terms of a conflict between mind and body, my Eigenwelt. The dissonance between my mind and body was acute in the early stages of recovery, particularly when seeing myself as an amputee for the first time.

Like an artist – visual or composer – I had to consider how I would reveal my ‘self’ to the world. Would I do so imprisoned in an unwieldly prosthetic device, an artificial limb? This was an aesthetically pleasing solution made all the more attractive by the pressure once again to be seen to have two legs and walk like everyone else. Or, would I be true to my remaining self, that is, what was left of me at the end of the day when I removed my prosthesis? My parents gave me the freedom to choose. Without knowing it they affirmed Tillich’s “essential doctrine of freedom”. At its heart this means you fundamentally belong to your ‘self’ as you know your ‘self’ to be. Knowing who that self is, is a gift: even if it may be mutilated and constitute a life-long challenge.

The terminology I use to configure my experience, namely Umwelt, Mitwelt, Eigenwelt has its home in the school of Existential-Humanistic Psychotherapy. Existential therapists understand people as a beings-in-the-world who construct their physical, personal, and relational worlds from their individual experiences and circumstances in the world. In particular, I have found the thought world of Rollo May, James Bugental and Irvin Yalom helpful in providing language in, with and under by which I can configure my experience of the world. It ‘fits’ my mind and makes sense in my philosophical disposition. I am unable to use ‘God-language’ as the narrative by which the fragments of life are woven together. When asked: “Do you trust God?” I immediately think: “To do what?”

The courage-to-be and to live in a form which is different from the ‘norm’ is a challenge for all those who find themselves marginalised; for example, as a result of physical illness, or mental health issues, or ethnic background, or gender orientation. This requires an act of courage-to-be, that is, the courage to accept oneself as accepted in spite of being unacceptable. Hence the crucifix becomes more important in the centre of my being than the concept “God”. In the Christian tradition, it is the existential form by which the divine chooses to belong to the world of fragmented humanity. The great temptation is to sanitize it, reduce its ugliness, and make it less appealing to those who know what suffering really is all about. If that happens, then those who suffer in all its myriad forms, no longer feel they belong. The biblical narratives inform us that the resurrected Christ is not perfect: The mortuary techniques of his day could not remove the nail holes and spear wound.

Neither have all artists over time sanitized the risen Christ. Creative interpretation allows a personal freedom to identify with the spiritual in us and the world. Art and music are possible choices through which we create structures for our self, or configure a window into our soul, thereby finding a form which is expressive of the self. We then place this into time and space for others to see or hear. In so doing artists and musicians construct their being-in-the-world and this choice requires a degree of courage. This bravery is apparent in this commended exhibition presenting both visual and musical creations which themselves, are inherently intertwined. It is a rare opportunity to full ones’ eyes and ears and enthusiasms.

Edwards, C (1989). Van Gogh and God: A Creative Spiritual Quest. Chicago: Loyola Press. p. 77.

Hughes, R (1990). Nothing If Not Critical. London: The Harvill Press, p. 144.